On Games Journalism – Valve’s Future

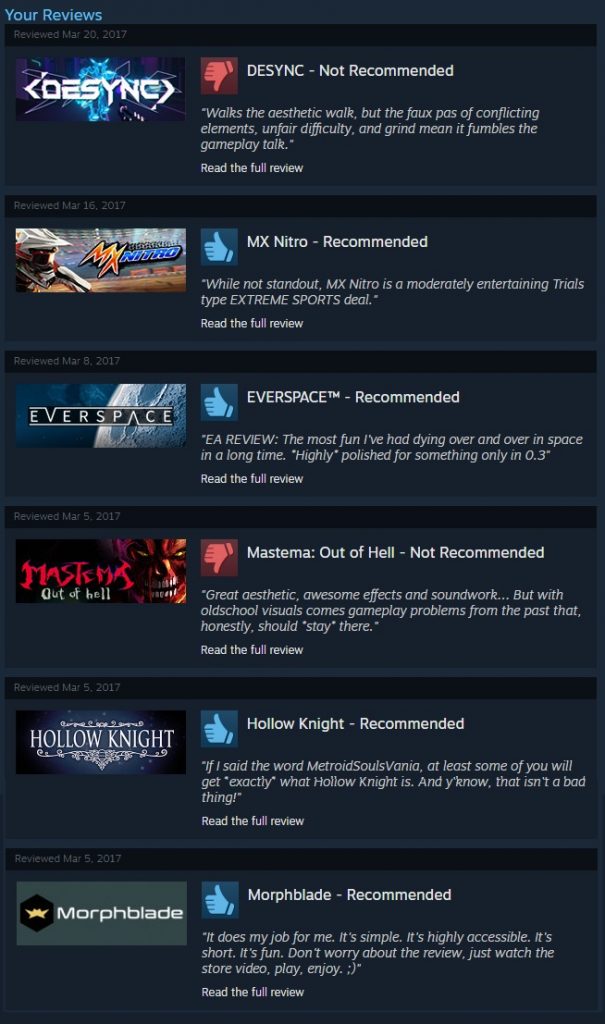

It’s interesting to note the changes to Steam being talked about by fellow game journalists (Relevant video links w/their names) Jim “Fucking” Sterling “, Son” , John “Total Biscuit” Bain, and, of course, many others, because, for all that TMW is a relatively small critical outpost, yes, these proposed changes, if they go through, if they work, may well be positive changes. So, let’s talk about a few of them, and how they could, potentially, make life a little bit easier for us games writers.

Cleanlight, and Steam Explorers

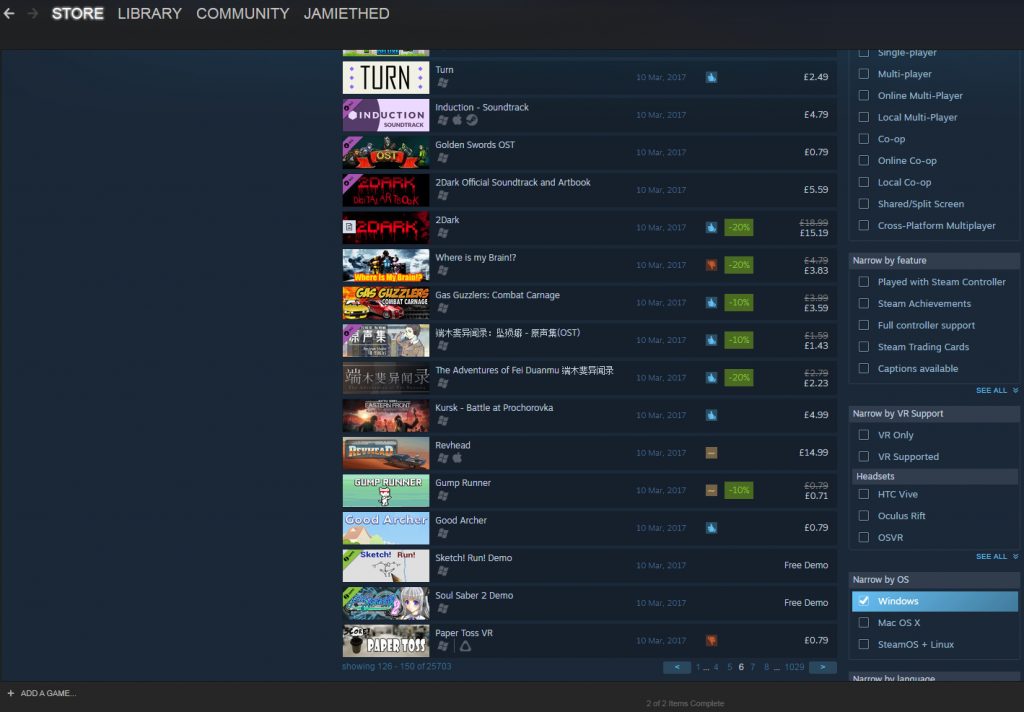

Greenlight, and the Discovery Queue in general, have not, sadly, been tools this writer has been using a heck of a lot, at least partly because… They’re not exactly terribly helpful to me. As noted in the previous On Games Journalism, my modus operandi, fortnight to fortnight, is to go through the “New Releases” tab (Easy as it is to fi- Ahahaha no, it only just passes my “3 interactions at max” UI test for games, and is not the most visible “feature”), and the Discovery Queue… Mostly tries to get me to try AAA games (Which I can ill afford), or things that, at best, would be good for a Going Back. At worst, I can go an entire Queue without seeing anything that even vaguely interests.

Nier: Automata. Critically acclamed, but sadly, too much for my wallet, and let’s face it, if you’re reading the site, odds are high you already like it. Also, I’d be a *tadge* late on that review, don’t you think?

More transparency in how it arrives at these conclusions would be highly useful. As to Greenlight, sadly, most of the time, I get my word about good things to greenlight via word of mouth, and it has been demonstrably proven that yes, there is an asset-flip problem. The news that Steam is tending toward lower figures on Steam Direct, and the frankly unsurprising revelation that bigger companies appear to have been tending against the lower figures, are respectively okay news, and unsurprising news.

So, as presented by Mr. Sterling, Steam Explorers is for exploring things with low sales that may (or may not) deserve such low sales. It’s not an initiative I personally expect to actually happen (Being, as has been noted in the past, a cynical auld so-and-so), but if it does, it definitely has potential. I’m somewhat more wary of incentivising the system, as that’s a sub-feature that definitely needs a delicate touch (Nothing so simple as “You get store credit for every X thumbs up”, because, let’s face it, that’s going to go tits up rather quickly. Extended refund time, however, would somewhat help.)

More Transparency!

As noted, it has also been proposed that more detailed game data would be publically available. How many buy the game? How many finish the game they buy? And so on would be very useful. I’m all for transparency, because, honestly, I can see quite a few benefits, and the countering of quite a few negatives. It’s useful from an academic standpoint, extra tools in a game historian’s toolbox. It’s useful from a reviewer’s standpoint, perhaps, if you look at the data, giving you fair warning that something does not, in fact, Get Better Later, and…

A prime bit of “Sizzle” from Nintendo’s BotW Review Roundup. GAME IS AWESOME (No Information Why.) Sadly, BotW is not on PC, and I don’t give Pretty Numbers, otherwise it would have gotten a 7/10 (Quite good, but not the Second Coming)

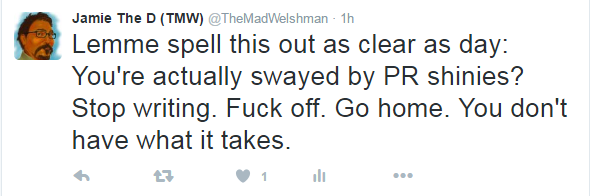

…It helps cut down on some of the shady bullshit that, sadly, happens. SURVEY YOUR COMPETITORS! By, instead of faking surveys to each other (No names named, but you know who you are), actually looking at the data. SOLD UMPTY MILLION COPIES… But returns are also noted, and right where everybody can see them. Along with the “Played for ten minutes, because the game was released in an unplayable state.” I don’t need to name names there, because said names have been shrieked to the rooftops from day one to week twelve, on average. Sizzle, that practice of content free fluff cherry picking the Good Reviews, could potentially be cut down.

All of this, sadly, is potential. We won’t know, until it actually hits, what form this could take. But you can guarantee I’m keeping at least one sleepy eye on that.

Curation Improvements?

I put a question mark here because Curation is one of those features that… Never really took off. I use it myself, but, right now, it’s another social media tool in my toolbox that doesn’t perform nearly as well as other social media tools in my toolbox. But, if what I’m hearing is correct, then it could well prove more useful. While also giving me more work. I’m looking at my current docket when I say that, and sort of sighing. There is such a thing as too much of a good thing.

But in any case, things currently on the table include better organisation and customisation of a Curator page, so, if you’re sad that you want to find a genre of game on TMW, but can’t (I’m still working on a good solution there, not helped by the fact that genre’s a little tough to pin down with a lot of the things I review), then the Curation changes might well help with that. I’m less enthused about “Top Tens” and other such things, due to my noted antipathy toward Pretty Numbers That Don’t Really Mean Anything Two Weeks Later, but hey, I’m sure that’ll prove useful to other writers who do like Pretty Numbers. Go them.

Part of last month’s curation. I mean, they’re good games, Danforth, but wouldn’t it be nice if you could look back and see what *else* I liked in that genre? Yeaaaah…

Also of interest is the idea of review copies directly being sent through Steam via the Curation page. With the possibility of refusal. This is a feature I’m fond of, not because it cuts down on the amount of work I do hunting said folks down and informally, but politely asking for review copies, but because it would potentially cut down at least some of the waiting and ambiguity that comes with said requests (Which is highly stressful.) As an aside, I love all of the folks who’ve replied positively, and especially the ones brave enough to reach out with something they think I’d like, but weren’t sure. Props to all of you.

So, it should be noted this is pretty brief. I’ve linked Mr. Sterling and Mr. Bain’s videos (and again!), which themselves provide their own personal opinions (And ones much closer to the ground floor, since they were invited to talks on these subjects), but… If these things happen, they definitely have potential, and I’m certainly willing to give all this a chance.

Just like Mr. Sterling, I’m not exactly hot on companies providing compensation for review as a feature, as I’d rather keep that to my already stated maximums, with a minimum of, of course, nothing. I’d much rather ensure that readers who like my work and my approach do that. Speaking of, there are ways to support TMW, and if you liked this article, maybe you should check some of them out?