The Eye of the Beholder Trilogy is a microcosm of the problems of the games industry, even today. Despite this, they’re still pretty much lauded among RPG players, with the exception of the third game, which has widely been panned, for reasons we’ll go into. So let’s go back, to the early to mid 90s, to see exactly why these games are both good… And why I said that first sentence.

D’aww, isn’t that Kobold adora- AHH KILLITKILLITKILLIT!

Eye of the Beholder was developed by Westwood games, who you may remember for the Command & Conquer series, and, if you’re old or savvy enough, the Lands of Lore and Kyrandia games. It was published by SSI (Who had a license from TSR to make Dungeons and Dragons games) in 1991, and, for the time, it was pretty good. In essence, it was a simple dungeon crawl beneath the city of Waterdeep, which had a big problem: An unknown threat (That totally isn’t a Beholder, folks!) wanting to conquer the city from beneath. As you travelled, first through sewers, then through ancient dwarven tunnels (Recently recolonised by some of said dwarves), and through ever weirder locales until you reached the Xanathar, head of the monstrous guild of the same name, and slew him. Along the way, you had hints of a larger plot that, for the most part, went unanswered. What was up with the dark elves (Drow) under the city, and their fight with the dwarves? Were they connected? What were these portals, and how did they come into the whole picture? Why did Waterdeep’s Sewers have a prison system, of all things inside it?

Meet one of the tenants of the “Correction Facility”. Next stop, the Death Room!

Part of this would have been the 90s “Rule of Cool” design (Where style over substance was the key), but just as importantly, the game was rushed. How do we know it was rushed? Because we can see cut content, if we look hard enough. And, since games were somewhat simpler back then, and state or save hacking was easier, it was completely possible to see hints of cut content, just by exploring empty space. For example, there is a stairway, from the lowest level to the highest. You can never walk to it without a trainer, and there is one final portal, with no missing slots for you to put one of the many portal keys you get in the game into. The official guidebook doesn’t even have them on the map. There’s other, smaller signs (Such as one of the surefire ways to kill Xanathar being hidden behind a “Secret Quest” that it’s kind of hard not to run into, or the somewhat abrupt ending, partly fixed in the Amiga and Sega CD versions of the game), but even reviewers of the time noticed it was incomplete.

Still, for the time, it was a pretty good game with a difficulty curve that nonetheless spiked rather hard toward the end, with some good enemy visuals, real time combat (Which was a slightly awkward fit with the spellcasting system… Right click on the spellbook/holy symbol and… Oh, shit, whole party paralyze from the Mind Flayer) and, despite the incomplete feeling, a surprisingly good story for RPGs of the time. I say this, in spite of the seemingly nonsensical placement of monsters (Kobolds on level 1, followed swiftly by undead, then Gnolls and Kuo-Toa, Spiders and Dwarves… ), because it was aimed at AD&D fans, and it was set in one of the more well known settings of the time: Forgotten Realms. Specifically, the City of Waterdeep, and the dungeon the city was built upon, Undermountain.

That Mind Flayer fires invisible all-party paralyzes, to represent his psychic powers. He has brothers.

That’s right, in a true blue example of Fantasy Characters Are Not The Smartest, they built a capital city on top of a massive, active dungeon. Several years before Recettear and other games lampshaded this rather distressing tendency. A shining example of Civic Planning in Fantasy Worlds, people!

Playing through it, at first, is a delight. It’s a simple setup: We’re sent to investigate the threat beneath Waterdeep (One of, it must be stressed, a multitude), and along the way, we find shining gems that defy explanation. The Sewer system has a small, forgotten prison complex inside it (With an execution chamber, hence the undead), and evidence of some pretty nifty, if badly applied fantasy technology (The Rapid Access Transport System… Teleporters for sewer workers. A pressure plate based flow management system). Later on, there’s a small, failing dwarven kingdom, besieged on all sides, but unable to ask the Lords of Waterdeep for assistance (And, as it turns out, hold a key to defeating the Xanathar.) Both the known henchmen of the Xanathar are treacherous (Shindia, and a threatening mage who sadly remains unnamed) , aaaand… While it’s absorbing, it’s bittersweet to look back and know that precisely none of those mysteries (Shindia led a group of Dark Elves planning to attack the surface. What became of that? What was with that “Museum” full of monsters in stasis? Had we upset the delicate balance of power in Undermountain?) are explained.

Outdoors! Finall- Eeee, wolves! Crap!

For the second game was to take place somewhere entirely different. Now, one thing about the Eye of the Beholder series (And many other RPG franchises of the time, such as The Bard’s Tale, Wizardry, Might and Magic, and a few other games, such as Breach and the rest of OmniTrend’s “Interlocking Games System” series) is that the characters can be preserved between games, and Eye of the Beholder 2… Depended on that. EoB 1 was an incomplete game (Albeit a fully working one). Eye of the Beholder 2 suffered from a second common problem in game design: Difficulty Balancing Issues.

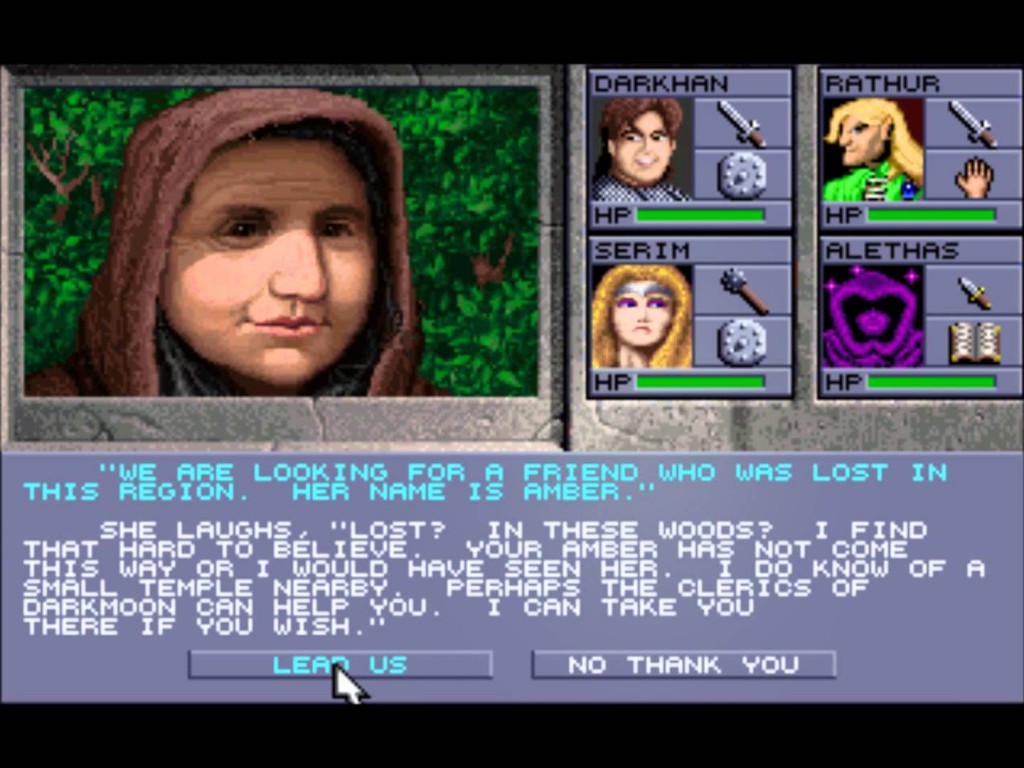

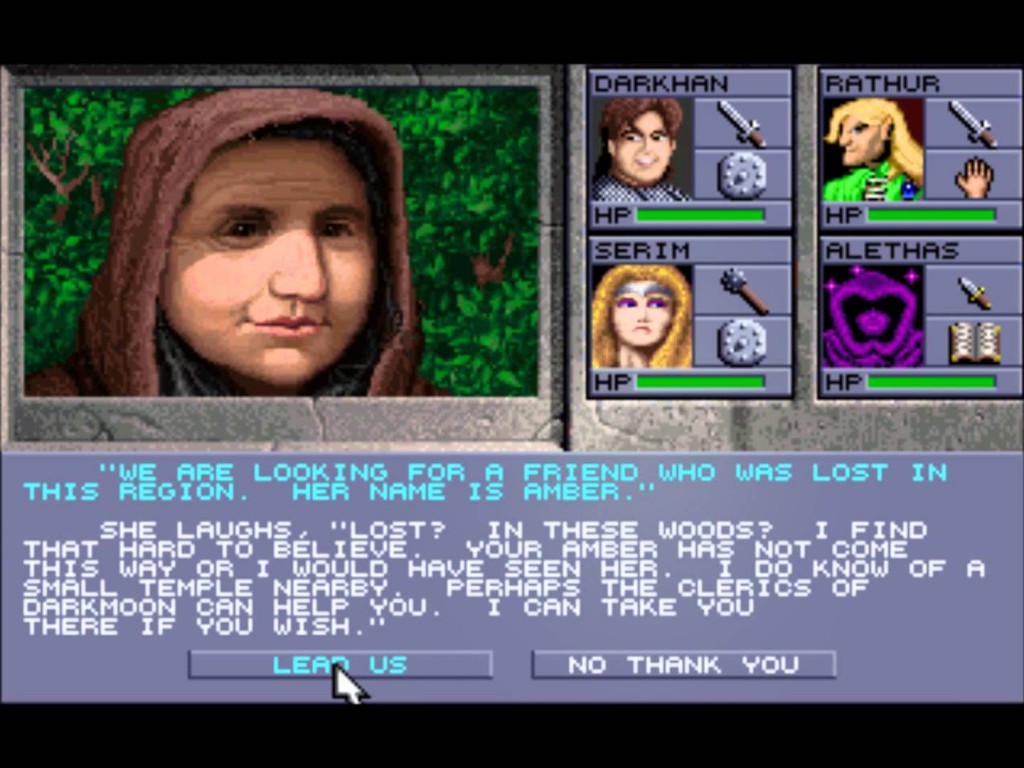

Eye of the Beholder 2, very early on, pitches you into a cramped room with sixteen skeleton warriors. It has an entire set of levels where you can’t heal, or regain spells. It’s a tough game to finish. But it’s still lauded as the best of the trilogy. Why is that? Well, partly rose coloured glasses, but it has to be admitted that Westwood stepped up their game on every front except balancing. More spells. More moments where your characters’ alignment/class actually means something (For example, if you try to dig up some graves you find in the first area, your Paladin will tell you it’s wrong… And then just straight up leaves if you push. No, I’m not going to tell you if it’s worth losing them.) Better music, and somewhat better visuals. The main villain is still a stereotypically evil cackling… Er… Skeleton Dragon (Dran Daggoran, or A Grand Dragon… sigh) with stereotypical, cacklingly evil plans (Build up a fake church in a world where atheism is a bad choice, gain an army of undead goons, rampage for a bit… ??? … Profit?) but the writing, overall, is better. Here, let me take an example from the beginning.

See! She’s so harmless… Like… That other lady, from Lands of Lo- Oh. OH…

There’s a nice old lady you meet in the woods who can guide you straight to the Temple of Darkmoon (Where your quest lies), avoiding encounters along the way… But, in a fit of Adventurer’s Paranoia, you strike her down. On her body is a single note. No, she’s not a mimic, or a spy… She’s a terrified old lady whose family is being held hostage. Well, now you know the temple is shady… But at what cost?

The Temple of Darkmoon, in a shift from the first game, is pretty self contained. Everything is to do with the quest, and there are no unexplained details that I’m aware of, and this actually adds to both the quality of writing… And the feel of isolation. You are definitely up against it, but alas, the difficulty really does spike in this game. Fought Xanathar last time without the oh-so-secret item? Had a hard time? How about multiple Beholders? Or timed puzzles? The ending, once it comes, feels less of a reward, being almost as perfunctory as the last game. Well done, said Khelben Blackstaff, High Wizard of Waterdeep. You stopped the evil plans, go rest for a bit in a pub, that’s what you adventurers do, isn’t it?

Sod you, Blackstaff. You and the rest of Waterdeep.

Yes, and you’re a 20/20/20 Wizard/Fighter/Plot Device , maybe, just this once, you can sort it out?

So we come now to the third game. The one that, of the trilogy, is widely considered both the worst, and part of the reason the “Legends” series didn’t continue. And it arose because of a third common problem in the games industry: Creative Differences. Now, that label covers a multitude of possible reasons for cutting ties with a studio, not all of which are actually to do with the creative direction intended, but, for whatever reason (I refuse to speculate, although I’m quite happy to be told), Westwood and SSI parted ways, with the in-house team creating Eye of the Beholder 3.

Visually, it was much better. The music was good, the cutscenes were good. But other things were… Not so good. No, let’s not mince words here. Other things were abysmal. Once again, you could import characters, and that was all well and good. But I hope somebody kept an axe, because without one, you’re going to be wailing and gnashing your teeth… In the very first area. At least until you firstly find an axe, and secondly, realise that large portions of the first area (A forest) can be cut away to reveal treasures, more encounters, and a dungeon. The game was relatively nonlinear, but the encounters felt weaker (With a few surprise exceptions, such as the Feyr… A mostly invisible monster. Thanks, folks, for reminding me to always have See Invisibility on… Or, y’know, flail in that general direction until it died), and the story.

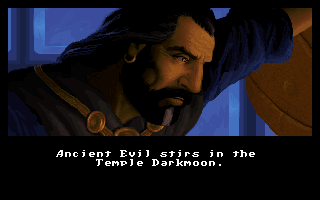

The story also felt weaker. Especially since you could see the plot beats before they happened. From the top…

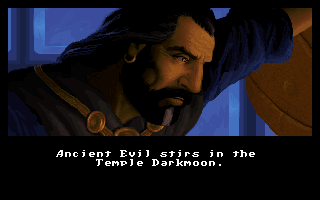

Yep, this isn’t in any way going to lead to resurrected evil gods, no sirree! That’s a trustworthy face!

…A totally not suspicious guy asks you to go to a lil’ place called Myth Drannor (Known among FR fans as a place where Ancient Magic and Things Not Meant To Be Woken Up reside) to kill a demilich (Known to be mostly good), which is guarding something Not-Suspicious Guy’s boss claims is endangering things.

At least one god (Lathander, the Morning Lord) has to help you clean up a mess that you, the player, knows is coming. Hell, the characters, being longstanding adventuring types, should know this is a bad idea. But no, you wake up an Ancient Evil, have to put it back in the box, and…

…Really, as in Wargames, the only winning move is not to play. The cutscenes are pretty, it’s true. But they’re the story of four to six folks doing something they should have known better than to do in the first place, then cleaning it up with divine assistance. The characters, rather than tied up in a cohesive plot, are split among the history of Myth Drannor, and… Don’t really have much to say, beyond what you already know (This Is A Bad Idea). All the extra nice bits, the new monsters, the pretty outdoors areas… They don’t compensate for this core fact. The difficulty curve, if anything, swung the other way to EoB 2… And the critical reception was, as I’ll get to in a moment, deafeningly negative.

Looks meaty… Not actually all that bad.

Good writing won’t always save a game. But bad writing, and frustrating design decisions can definitely help kill it. Reviewers at the time disagreed with my note on the visuals and audio, and, if anything, were more disappointed than I am, looking back after some years. It was seen as a Cash-Grab (ding), a disappointing end to a series, and it was unequivocally seen as an end. They were perfectly correct. Apart from the remakes of the first two games, the Eye of the Beholder series was dead, dead, dead.

Now, for all my talk of the games showing that problems have existed in the games industry for some time, and are by no means new, does that mean they’re bad games? Funnily enough, no. Just as some games have their flaws, but are still enjoyable (And indeed, enjoyed) by many, the Eye of the Beholder trilogy is enjoyable. You can even try them yourselves, thanks to the wonderful folks at Good Old Games. They even come with the official cluebooks and manuals of the time, which are themselves worth commenting on, because they’re good examples of such things done pretty well. I have fond memories of the first two games, and, when I feel I’m confident enough to tackle them, will definitely try to Let’s Play the trilogy, warts and all.

But I wonder how things could have turned out differently, sometimes.

Filed under: Games Gone By by admin

Become a Patron!