Let’s Talk “Tough”

Okay, so this past month has seen, seemingly, the unwelcome return of “Oh, but this is challenging!” to the Mad Welshman’s hearing. And I’m getting rather sick of the phrase, because it often disguises just plain bad design. So let’s talk about some common pitfalls here.

It Gets Better Much Later!

“It’s okay, it’ll get better later!”

“Well, that’s a shame, because it’s dull, repetitive, and shitty *right* now, and I’m tired.”

This is what we, in the criticising/design end of things, like to call a “Difficulty curve problem” or an “Interest curve problem.” If you are having to tell me that the game gets better later to keep me playing now, then something has gone wrong. And usually, it’s not understanding what makes a challenging fight challenging, or an area/encounter interesting.

A challenging encounter is one where you are given time to understand the rules of engagement, but will still get your shit wrecked if you don’t have the skill. The Asylum Demon from Dark Souls is a good example of this, as you can run away quite effectively for some time (In fact, the fight is optional the first time through.) He swings. He butt stomps. He telegraphs. That last bit is important. Equally important, even though it doesn’t seem it, is that you know what effect you’re having.

An uncomfortable encounter would be one where there are wrinkles that you would be unaware of until the fight is underway, causing problems down the line. A good example of this would be from the Persona series, where a specific encounter, Nyx/Night Queen, will charm your healer, who then… Heals said encounter up to full health. Because it’s relatively pattern based, it can be planned for and countered, but it’s an unpleasant surprise that can lead to a slow death and frustration the first time round. Hope you saved!

A bad encounter is one where nothing is telegraphed, or there’s something for which you have no counter beyond memorisation and/or flawless execution. An example of this would be Mind Flayers from the original Eye of the Beholder, whose awesome powers are represented by… An invisible ranged attack that can cause an all party paralyse, aka “Might as well be a game over.” Not even a late game enemy needs something like this.

Interest, unfortunately, is much harder to gauge. Even an engagingly written Wall-O-Text(TM) is going to turn some people off, whereas a five minute cutscene might have people sitting on the edge of their seats. But there are some things that aren’t recommended, and I’ll go into some of them a little further on.

The Last Place You’ll Look

This one can especially be a problem for exploration games, like Metroidvanias, but some people just don’t get that many players will do anything, anything rather than look somewhere they’ve been discouraged to. This is one where I’m not going to name names, but give a possibility, to show you what sort of things you really want to avoid.

The first, and best, would be the Heat Suit in the Lava Place. Okay, so on the one hand, props for thematic placement… But I’m not talking about the edge of such a place. Oh, no. We’re talking at the edges of your health requirements. We’re talking a case of “If you have X health powerups, and pass the obstacles along the way well (or flawlessly) while taking the damage over time from over heat, you’ll be able to get the Heat Suit, which stops that damage over time effect.” A perfect example of this was provided by one of my twitter followers, where, in La Mulana, the Ice Cape (Which reduces lava damage) is at the end of the Inferno Cavern (Which not only has lava, but fireballs that will often knock you into the lava.)

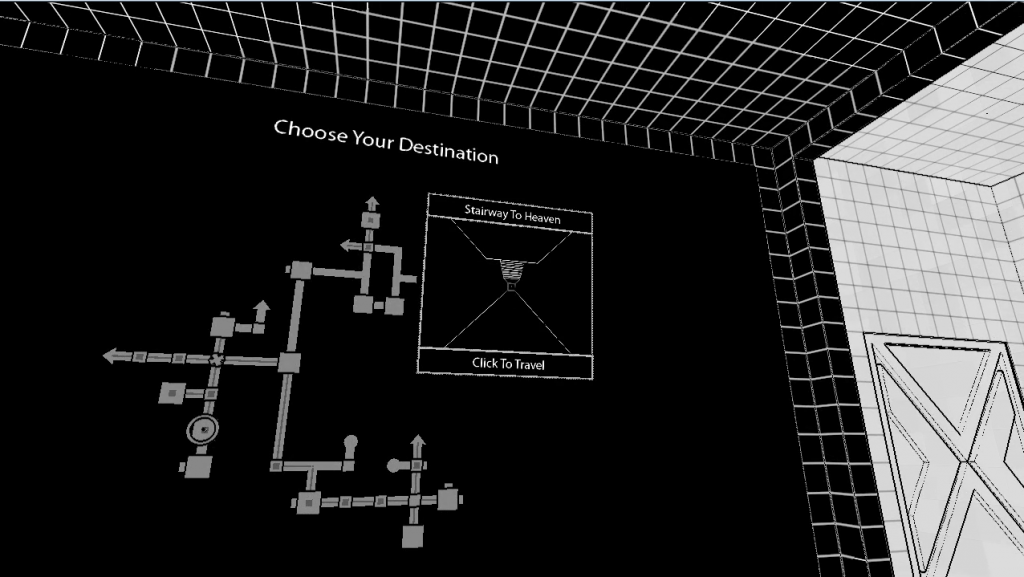

Don’t do this. Don’t ever do this. First off, what the heck is it doing all the way there? How did the normal schmoes get it, before everything went to hell? How did it get there? How will anybody know? And this applies to a lot of things, because players can be easily discouraged. Let’s say there’s something that jams your minimap. Let’s say knowing where you are is kind of important. Players won’t want to explore that jammed area until they know how to deal with it. If the thing you need to deal with it is in that area, then congratulations, you have basically created an old-school game maze, a piece of artificial padding that’s been despised since… Well, a long damn time.

While we’re on the subject…

The Maze. Because.

Welcome to the Brain Maze. This is something like what you’ll be seeing for the next half hour. Enjoy!

That “Because” is kind of important. Putting a maze in your level design for no good reason is going to annoy people. Especially if it’s a teleporter maze, where there’s no frame of reference. Especially if you can’t leave some sort of breadcrumb trail. Especially if you can’t pick those “breadcrumbs” back up again, and need them.

Realms of the Haunting, for all that it had a strong, interesting early game, suffers really badly from this in the latter half. At least two hedge mazes, at least two cave mazes, and a couple of maze puzzles. That game suffered because of that. Yours doesn’t have to. Yes, there have been clever mazes (And clever pseudo-mazes.) That doesn’t change the fact that often, it’s a lazy puzzle.

The Random Chance of Instant Death

This one mostly applies to RPGs, but there’s an analogue in some strategy games. Essentially, sometimes, monsters in games have a random chance, if they hit you, of straight up killing you. Often, this goes along with random encounters, or scripted, yet invisible encounters. So you walk into a fight and… Oh, bad luck, hope you saved before that fight!

Yeah, nobody’s going to ever claim that was fair. Or much of a challenge on either side. Either the insta-death doesn’t proc, and the monster wastes its life trying to kill you, or it does, and you’ve got nothing left but to reload an earlier save. I could point to an absolute multitude of early RPGs that do this, including… Er… Most of the CRPGs of the 80s and 90s.

Thing is, this applies to pretty much any game where you can be dicked out of a victory by nothing more than chance. Need to roll seventeen sixes on 20 d6 to win a game? That’s bad. On a related note, you have the…

Gotcha PowerUp

Oh, that extra life looks really tempting, doesn’t it? Shame that if you try and get it, you’re going to die. Well, chalk that up to learning a lesson abo- What, you thought you didn’t have to go through that tough segment it’s at the end of again? Ahaha no. Go directly to checkpoint, do not pass go, and do not collect your extra life. To make it worse, sometimes it’s not an extra life. Sometimes, it’s not even a real power up. When you just can’t reach it, ever, that’s lacklustre design. When you can, but can’t get anywhere without dying? You’ve been Gotcha’d, and it’s bad design.

Gotcha Enemies/FUCKING BATS/Gotcha Spikes

There is a reason Castlevania bats have mostly gone out of fashion… Because everybody knows they’re difficulty padding. For those who don’t know why bats (or birds, or spiders, or medusa heads) are considered such a bane, let’s consider a jump. If you are skilled, you will make that jump. Okay, that’s fair.

Now add knockback on a hit from an enemy or obstacle. Put that enemy in the middle, and make sure it dies in one hit. Okay, now it’s challenging, because there’s a timing element too.

Now replace that enemy you know with bats. There is never one bat. They either move toward some point on you (Often below or above your weapon’s hitbox), or they move in a predetermined fashion across the screen from a random point. Congratulations, you’ve just gotten pissed off at the fifth time you’ve been knocked into that pit, and very possibly died.

Another variant of this is the Gotcha Enemy, the one that is either on your target platform in an obstacle course, or appears just as you’re about to land. Unlike the other examples, it can’t be killed in one hit. So you’re going to get knocked back unless you have some other resource to deal with it… You know, into that pit. Which kills you.

But let’s say it doesn’t kill you. This gives us an example of the Gotcha spikes! You fall, and, holy of holies, there’s a platform, you’re not going to die!

Except you are, because you can’t control your movement while being knocked back, and you need to go right, not left to land on it. Everywhere else is spikes. For extra dickmovery, let’s imagine that platform is actually where you need to go to complete the level.

You’d think this was me making things up. But no, these are things that have happened in older games before. Mostly in the Mega Man and Castlevania series, both of which are well known for their equivalents of FUCKING BATS (Which, in Castlevania’s case, is where the term came from.)

Read My Mind.

This one is particularly bad with adventure games and RPGs, because it’s long been accepted that both genres can have puzzles, and maybe should have puzzles… But the art of designing a puzzle is a tricky one, because not only do you have to know the solution before you write it, you have to think really hard about whether you would, in the situation your character is in, arrive at that solution too. We even have a name for it, based on a game by Jane Jensen (Who normally writes much better puzzles, to be perfectly fair): Cat Hair Moustache. Of course, this includes a multitude of sins, including bad signposting, bad logic, and lack of clarity.

Gobliiins, by Coktelvision, has entertaining animations, endearing characters, and only got better with the addition of music and cheesy VA. However, it suffered from all three of these problems, and it was only made worse by a health bar system that would lose you the game if you screwed up enough. Hey, maybe punching/magicking/using this thing would he- Oh, wait, no, it dropped our health bar because it was secretly full of snakes/spiders/a possibly undead gribbley. One of those things, by the way, was an integral part of a puzzle, but if not handled in exactly the correct way, would give you a game over quite quickly.

Some of the hidden rules behind Gobliiins you learn quite quickly (Never ask Dwayne to use a stick shaped object on anything but the thing he’s meant to, or he will bash himself on the head.) Others, you can never be certain of.

And so it becomes a game of trial and error, because there is only one solution (Sometimes two), and sometimes, it involves moon logic (Such as opening a cupboard by throwing a dart at a picture of its owner) or just guessing which one is right (Which apples are safe to make big and carry to fill a gap in a bridge?)

I’m Not Going To Tell You

Sometimes, you don’t actually have the information you need to make a solid decision. This one comes in several varieties, but the core question in each of them is “Should I, as my character, know what I don’t know?” If the answer is “Yes”, then you have correctly identified the game padding its difficulty. Unfortunately, part of the problem here is that, a lot of the time, you don’t know it’s there to be important. For example, ally kills in Disgaea bar you from the best ending, but the criteria for it? It’s somewhat picky.

Now, I want to be completely fair here, and mention that, in one particular case, it’s because of factors outside the developer’s control. Specifically, copyrighting of sanity meters. That’s right, that whole “Your vision gets fucked up when looking at a creepy thing” comes from designers having to get around paying extra money because they can’t give you a number to tell you how scared you are.

Checkpoint: Failed

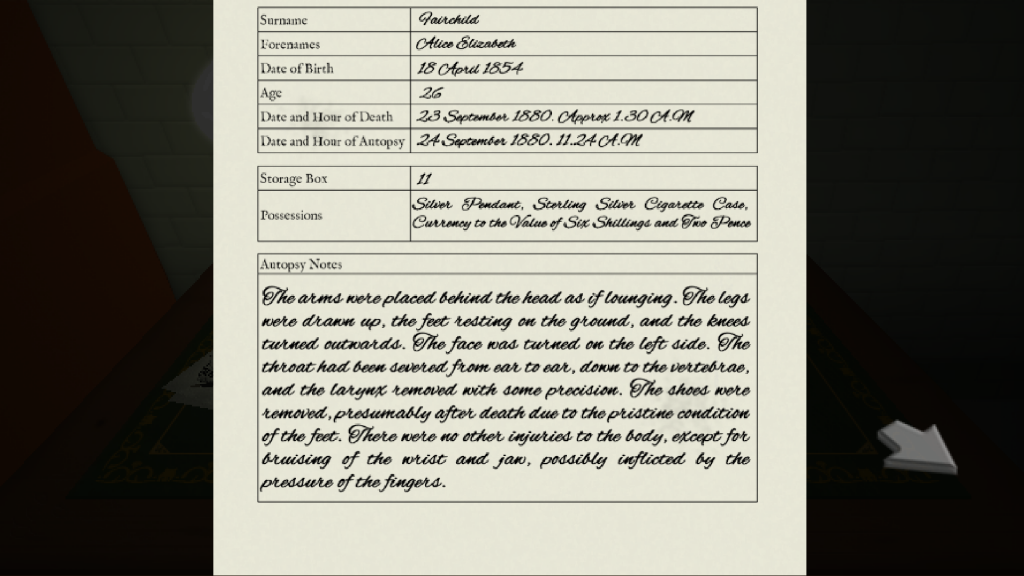

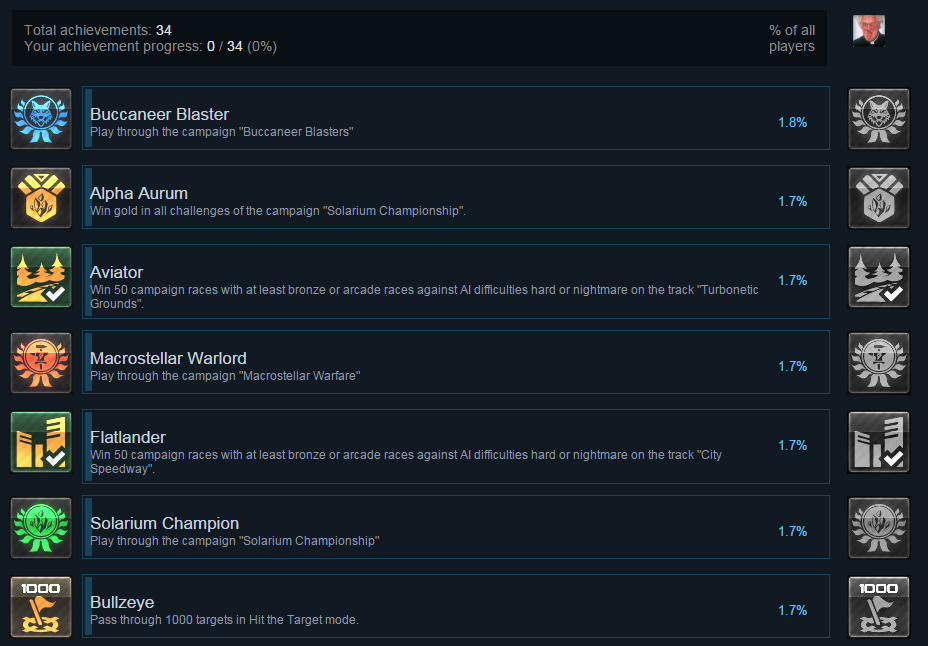

Not actually a *terrible* example of what I’m talking about. But there’s lots of them out there, even today.

Hoo boy. This is a really common one. From the multi-stage boss without a checkpoint, to the one button runners without a checkpoint, ignoring checkpoints if your game is already challenging (or just plain difficult) takes it to a whole other level of fuck you. Let’s take the one button runner example. There is a game, that I will not name, which has a cool soundtrack, some great customisation, acknowledges that colour blindness is a thing, and has some cool set pieces within its limited repertoire. But none of this is very useful, because, since not a single level has checkpoints. In game, I’m hearing the same thirty seconds to a minute (On a particularly bad day, 15 seconds) over and over again, I’m not seeing most of the set pieces, and due to this, I have a playtime of… An hour, gained in ten minute dribs and drabs once in a blue moon, since I bought it two months ago. I have beaten two levels. Is it because I’m bad at the game? No, it’s because a one-button runner is already a challenging genre, and having not a single checkpoint in a five to ten minute level requiring quick input and pattern memorisation pushes it from “Challenging” to “No, fuck you.”

Things To Keep In Mind

A clever designer can make these things not seem so bad. Well, most of them. Hidden stats, for example, are pretty much “flavour” in many racing games, and you don’t need to know the hidden stats to play Pokemon. Sometimes, they’re limitations. But they can nearly all be taken out of your game, if you make one, with just a little forethought.

Ask questions as you design.

Ask folks to test your game, and watch folks playing your game. They will surprise you.

Look at older games, and learn from their mistakes.

Don’t blame me for any complaints if you don’t.