Going Back (?) – The 8-Bit Adventure Anthology, Volume 1

Source: Review Copy

Price: £5.79

Where To Get It: Steam

Adventure games have quite the history, and it’s one with a lot of branches, and, interestingly enough, more than a couple of roots. For example, while it’s commonly accepted that CAVE, which was eventually renamed Colossal Cave Adventure, was the progenitor of Interactive Fiction (Due to the fact that anything earlier has been lost to time, it’s intriguing to note the history, as adventure games with graphics cropped up as early as 1980 (With Sierra’s Mystery House), and games with a point and click cursor (Controlled by the keyboard) came around 1983, with Project Mephius for the FM-7, a computer that released only in Japan. Indeed, part of the reason the timeline of game design is so messy is that European, American, and Japanese markets had their own home grown items that none of the others saw (Until later.)

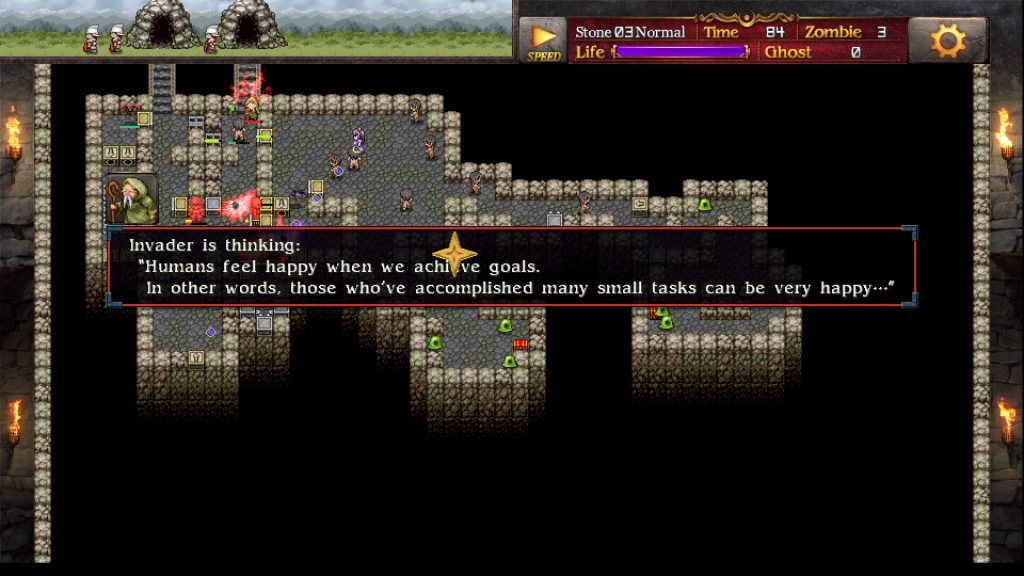

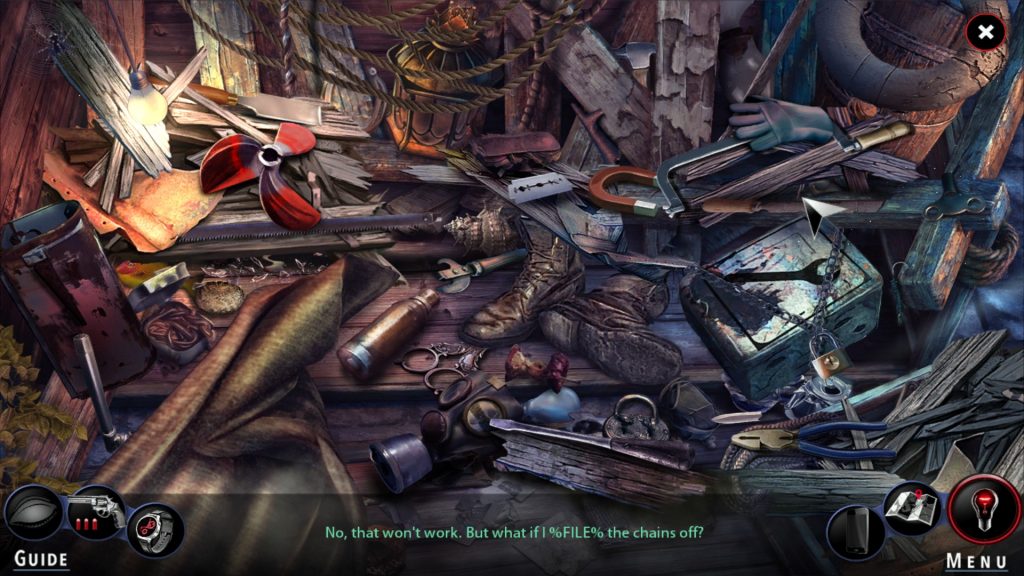

Okay, so I’ve uncovered this… But how the heck do I open this door to the left? HRM.

Why all this preamble? To establish two things. That the adventures comprising this remake anthology are not, strictly speaking, firsts in the genre. Influential games, yes, but not firsts. But also that it’s fascinating to see changes and shifts, not just on the purely international level, but within individual nations. We’ll be briefly coming back to this, but first, the games!

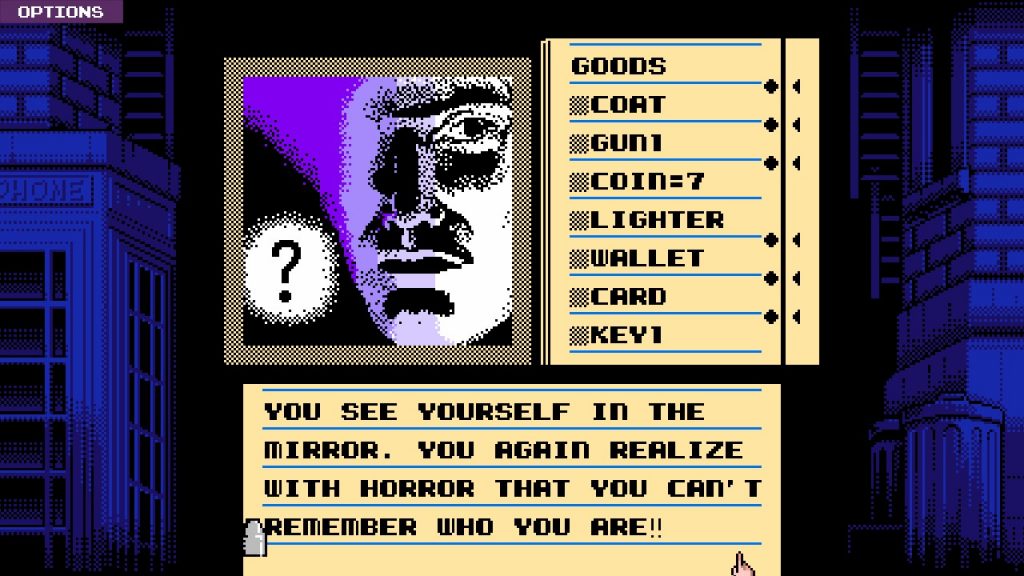

The three games that comprise this trilogy were originally created in the mid 80s (1985-87) for the then humble Apple Macintosh, and, as such, were known as the MacVentures: Deja Vu, a noirish tale about an amnesiac detective down on his luck; Uninvited, a haunted house tale with the main character searching for their younger brother; and Shadowgate, a fantasy yarn that, despite the comparatively higher difficulty of the former two games, has a reputation for its gotchas and deathtraps. They had a graphic user interface, a selectable parser, and an icon based inventory, all of which were not, strictly speaking, new… But they might as well have been to the European and American audiences.

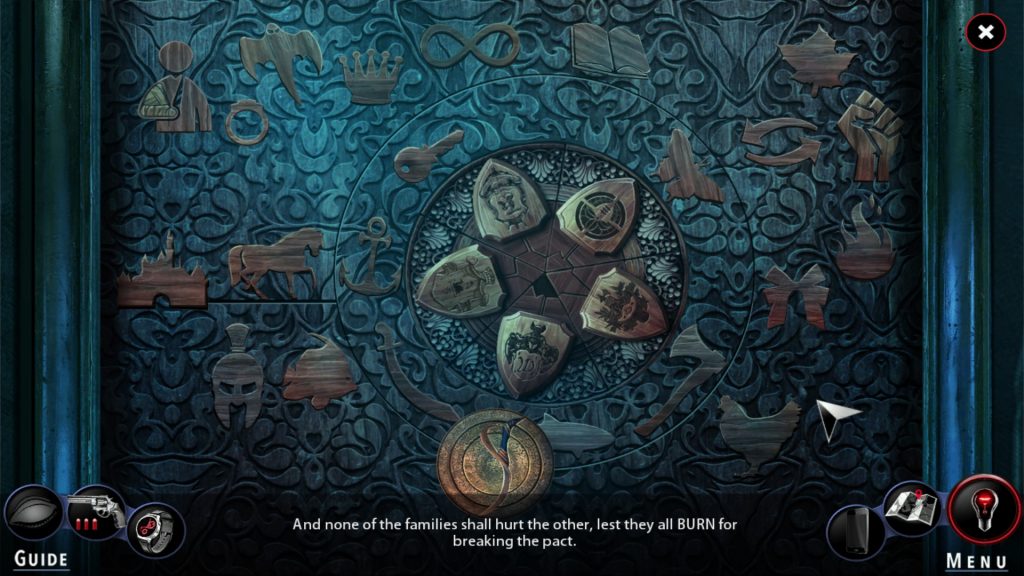

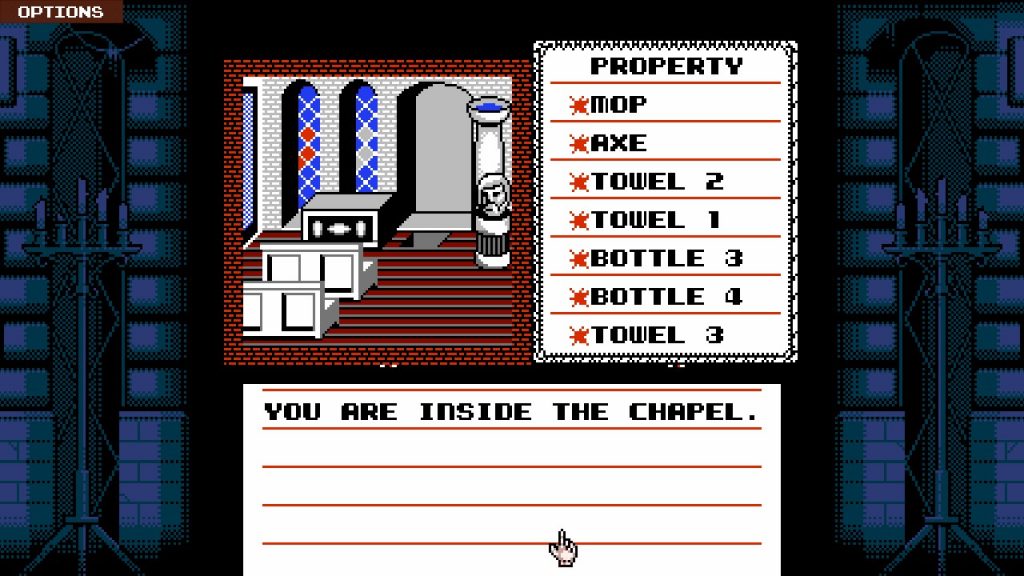

They did pretty well, well enough that a company called KEMCO ported them, with permission, to the Nintendo Entertainment System in 1989 and 1990. These are the games remade and presented in this anthology, and this, also, is interesting because the UI was changed, a controller led pointer was introduced (as in Project Mephius, several years previously), and Nintendo, a family friendly company even then, asked for… Changes. Some of these changes, I’m sure people are very grateful about: As far as I’m aware, the ten minute timer for one of Deja Vu’s “Solve this or die” puzzles (finding a cure for your amnesia) was gone. Yes, ten real time minutes. The interface was made tighter due to platform limitations, pentagrams were replaced by stars, and crosses by chalices, and, in an odd decision, it’s not the younger brother you save in Uninvited, but an elder sister.

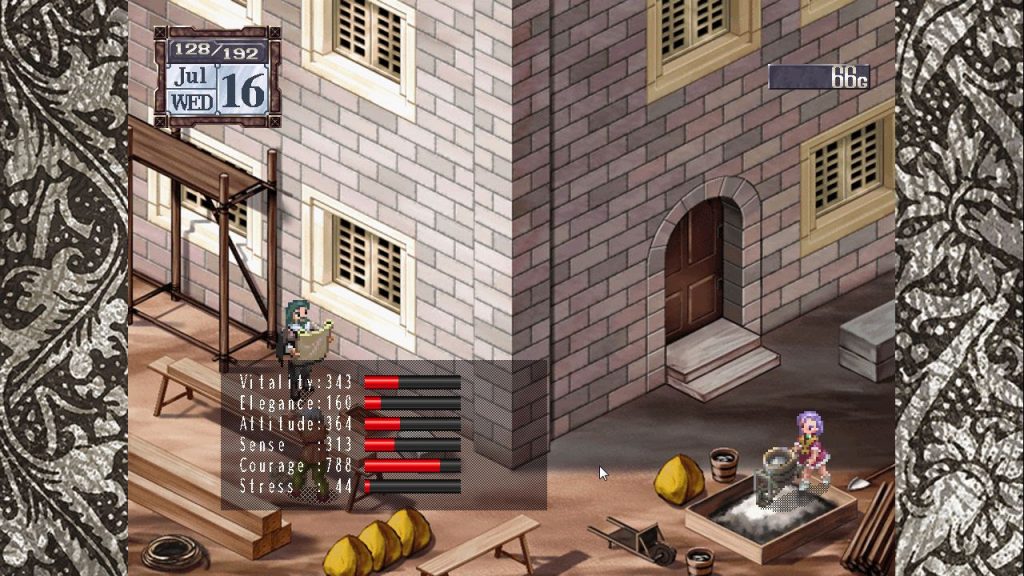

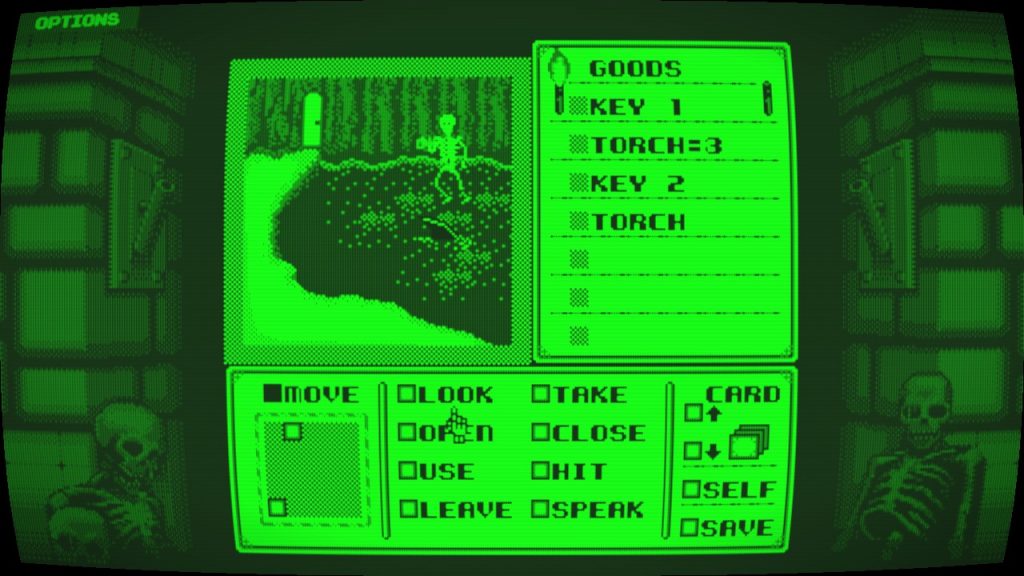

Yep. That is indeed a greenscreen terminal filter. Yessirree.

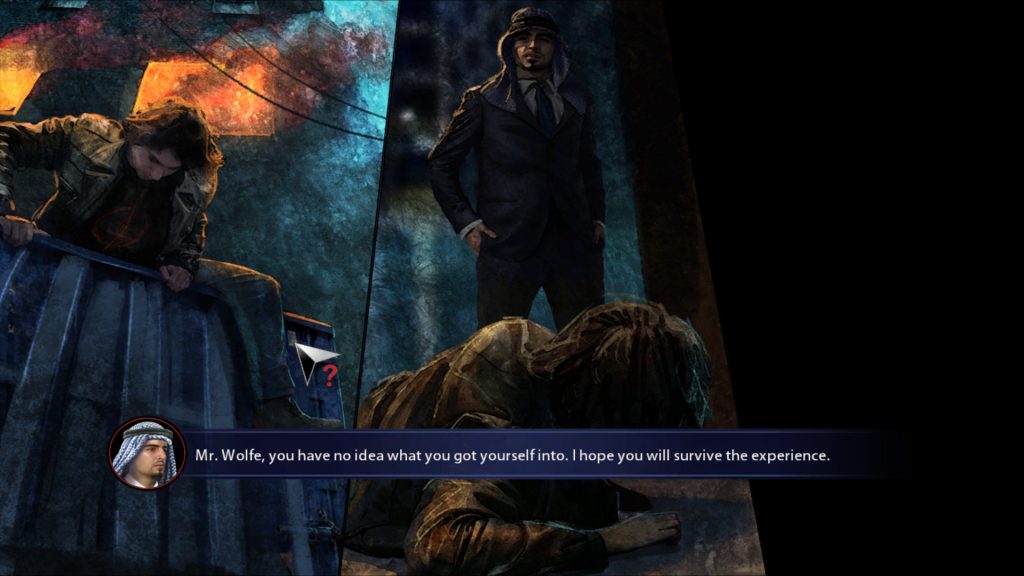

In any case, that’s where we are today: Reviewing a port of a port of a trio of adventure games from the 80s. How do they hold up? Not that bad, actually! The Nintendo versions were not only notable for their changes, but a solid soundtrack that still holds up to this day, distinctive spritework, and an interface that, thanks to the fact we’re using a mouse rather than the NES controller, is highly accessible and a delight to use. Each could be played through over the course of an afternoon, perhaps less if you follow the ancient adventure game maxim of “Save Early, Save Often” , and only a few of the puzzles don’t have some signposting to their solution (There’s no clue, for example, that a certain ghost is afraid of spiders, sadly.) Be warned, however, that garbage items with no actual use in game abound. Old adventure games loved to do that, partly for realism’s sake (Yes, even then), but also partly to obscure solutions.

Being able to keep saves, and switch between them with relative ease? Oh yes, this is good. Having… Old monitor filters? Well, I guess it’s there? (Not gonna lie, if I wanted more eye strain, I’d just dig out my old BBC Micro and its CRT monitor. But they are nice filters.) And the writing of the games, for the most part, holds up. Deja Vu, being both a game of the 80s, and being inspired by the pulps, is perhaps the one that has aged most poorly, but there’s still some solid design there.

Also, the achievements. Ah ha ha yes, the achievements! It somewhat tickles me that the achievements for this trilogy all have to do with something you would either, unaware of this game from its heyday, stumble into, or, if you’re like me, a person amused by the death states of old videogames, actively seek them out: The deaths. Wait, you mean that lady wasn’t friendly? Gosh! And my shield could only take a few puffs of molten, superheated death spewing from a dragon’s mouth? Golly!

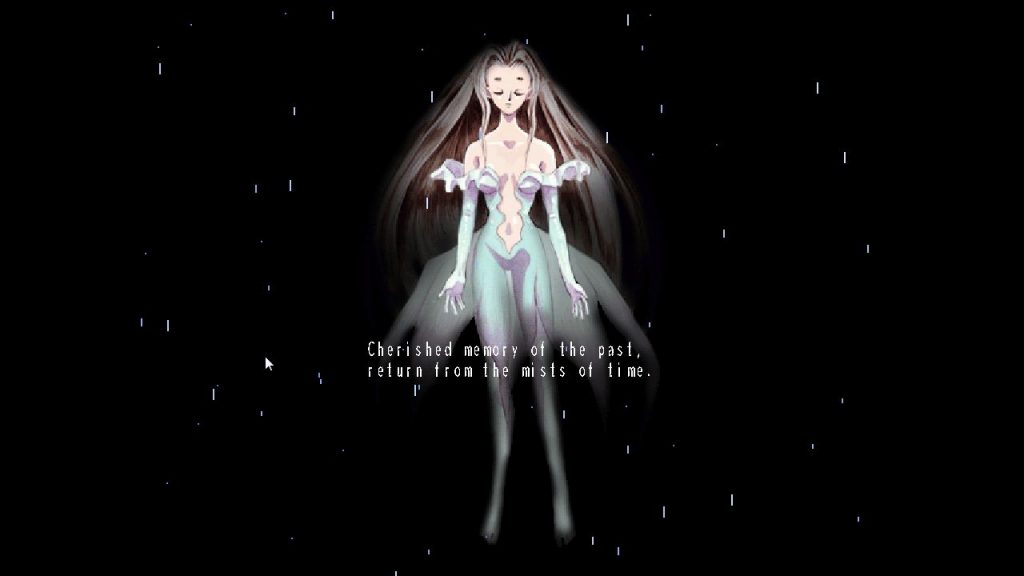

Well, we know we’re a dude. This much, we can be sure of.

As pieces of relatively faithfully preserved games history, this isn’t bad at all, although the “Volume 1” confuses me a little. After all, there were four MacVentures in total, so… Where would you go from here, General Arcade and Abstraction? Although it must be said, this trilogy did seem to inspire a wave of graphical adventure innovation in the West, from the Legend Entertainment games, to the Magnetic Scrolls series, each of which contributed, somewhat, to the eventual rise of the point-and-clicks we know and love today.

So yes, give these a go if you feel like experiencing some relatively solid 80s game design, and perhaps it might inspire you to check out other bits of adventure game history (Or, indeed, some of the other ports existing out there.)

The Mad Welshman enjoys older adventure games. Things tend to happen when he BITE LIP, however. Terrible things.