More Learnings From Game Design History

Last time, we took a (very brief) look at BBC BASIC, and just a couple of the things it could teach us, the modern game developer. Today, we’re going to look at games themselves. Games of the past. Games that, sometimes, fairly or not, have been dumped in the rubbish bin of game development history, because, let’s face it, we’re not very good at this whole “Preservation” thing. We’re going to categorise this by lesson, because otherwise… We’d probably be here a long time.

You’d Be Amazed How Much Can Be Boiled Down To “Lemonade Stand”

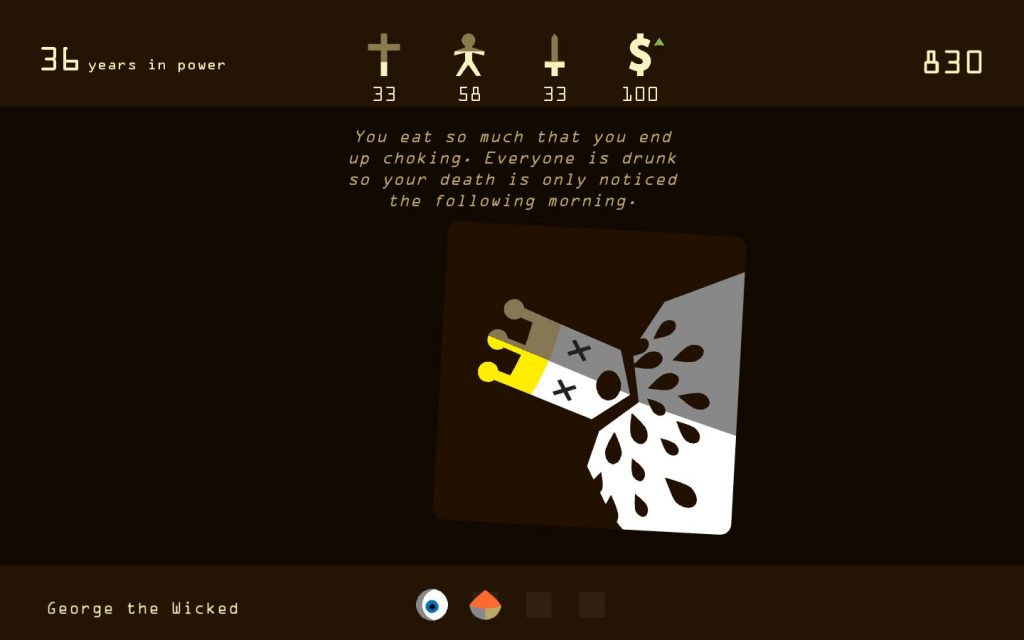

You partied so hard you died. Because you had all the money. Haha on you for being so good at Lemonade Stand! XP

Lemonade goes by many names: Lemonade Stand, Apple Seller, Beer Merchant, and other combinations of [Noun] [Place or Person where Noun could conceivably be sold]. You judge how much of a thing to make, based on how much money you have, and how much you think you’ll earn, and then you earn an amount greater or smaller, because a random element has been introduced. Or it hasn’t, and it becomes a simple math problem in how to most efficiently bilk the customers of your foul tasting lemonade. You cad.

It is, in essence, a game about wanting numbers to go up, using numbers. It’s a game where having no numbers (or not enough numbers) is a fail state, and having too many numbers is, in a way, a fail state. Because who wants to keep playing Lemonade Stand forever?

But a lot of games use the basic ideas of Lemonade Stand, even today. It’s just they use different bits, and they use them a lot. Let’s take a look at Reigns. Beautiful game, wittily told, with a solid aesthetic. But, mechanically? It is a game of keeping four sets of numbers in between two numbers, with the random element that you don’t get to (directly) choose what event is coming. Too low, or too high, and nope, no kingly lemonade stand for you, only a messy death. And the immediate chance to go again.

Okay, let’s go back a bit further. Princess Maker is a game that’s all about its pretty numbers. This time, you generally know what your money is going to get you, in terms of your several varieties of lemonade. Generally, as how much money you make (for more lemonade) depends on how much lemonade (If you haven’t twigged yet, I’m talking about your stats) you already have. Sometimes (in the one I know most about, 2, anyway), a pervy demon will randomly appear and ask you for some pure lemonade in exchange for his stanky, thirst inducing lemonade. And some money. Having enough of the right types of lemonade, at the end of your game, will earn you one of its many, many endings. Good luck working out how you got there.

Cook, Serve, Delicious is Lemonade Stand with actual customer preferences, and a skill based system that means, no matter how much money you sink in, if you aren’t good at typing certain keys, in a certain sequence, very quickly, you won’t get money for your lemonade, and nobody will want to come to your lemonade store.

Of course, by now, you’ve probably noticed how specious, and, in a very real sense, reductive this argument is. This has a point, and the point is: A lot of what you’re going to do, in a game, can be boiled to numbers going up and down. Some numbers mustn’t go down, others mustn’t go up, and sometimes, the numbers have to be kept balanced. While numbers are the pistons that make your game move (considering how movement is, itself, a mathematical operation, and you will be using Sines a lot, this is extremely true), and they form the groundwork of your game, they are not, generally speaking, where the magic happens.

Sometimes, The Baby Has Been Thrown Out With The Bathwater

Captain Blood: Not a good game, but pictured is one of its better ideas.

Captain Blood is, on the face of it, not a good game. It’s hard as balls, often arbitrarily so, you can easily end up in Dead Man Walking scenarios (Where the game cannot be completed, but it doesn’t tell you this), and conversations can often end up very circular.

Thing is, I’ve never seen its conversation system replicated since, and this is a shame, because it boils things down to simple concepts out of which it constructs sentences, according to its plan. Part of this is that Captain Blood is, as is, a somewhat obscure game. But once you play it? Ohhhh, what a headache!

And so, because the game was bad, this otherwise perfectly usable (and potentially quite interesting) element has largely been lost.

Similarly, Millennia: Altered Destinies has a core conceit that’s fascinating in theory, but difficult and unintuitive in practice: It’s a 4x/Adventure hybrid in which not only space has to be considered, but time. The key races have to survive to at least the point of developing one of the ingredients you need to destroy a space-time spanning menace, and it’s preferable that as many as possible survive so you can destroy this all encompassing death once and forever. Unfortunately, the interface is a bit of a mess, it’s somewhat hard to grasp what’s going on, and so, once again, a concept is, as far as I am aware, still up for grabs.

Sometimes, I’ll freely admit, I’m happy that certain ideas have been thrown out. In at least some cases, they’ve changed, and, honestly, for the better. Remember splitting the party in a real-time game? Ohhh, that was a thing, alright. A thing I never actually wanted to do. Some, like the mid to late Ultima games, handled this relatively well (characters would either stay in a certain place at the nearest town, or go back to their starting point, ready for retrieval whenever needed.) Others, like Syndicate, kept this limited enough that it was still easily doable (Although knowing the mission’s surprises beforehand definitely trumped being tactical.) But some handled this badly enough that yes, I’m glad this has largely metamorphosed into things like drop-in co-op.

There are many games out there, enough that playing all of the Atari ST’s back catalogue alone could take me several years… But it’s worth looking at games of the past, for the ideas that have fallen by the wayside, maybe part of games that, while you disliked the games, the idea still stuck with you. Just because a particular kind of game is considered “dead” (Rightly or, more often, wrongly) doesn’t mean it’s devoid of things you can be inspired by.

An Interesting World Goes A Long Way

Diddlydiddlydiddlydiddlydiddlydiddlydiddlydiddlydiiiiiiiioommmm… (Even the music’s stuck in my head)

I will never not remember Harlequin as better than it actually is. A platform adventure game, involving solving switch puzzles (some of which were connected to entirely different levels), with a final area for the “true” ending that’s infamous among people who actually managed to get that far (and not, for example, got stuck in trying to work out what the deal with Heaven was, or found themselves at an impasse because they didn’t know about TeeVee Wonderland’s level), it nonetheless holds a shiny, warm place in my heart because Chimerica made a twisted sort of sense. The same twisted sort of sense you’d see in… Ooh, a dream. Something existing only as the product of unchecked imagination… Dare I say it… Chimerical. Where had the people of Chimerica gone? What had gone wrong with this world? I needed to know.

Meanwhile, I’ve written an entire article on how RPG worlds often need to do more, specifically picking on Dungeons and Dragons properties because I already know the interesting bits of their worlds, and not a whole lot of them are explored in the games. Dark Sun is a harsh land, a land where magic has slowly killed the world, water is more of a currency than the ceramic coins common to its noted world… And the coins are ceramic because metals are both rare and not a good idea to wear, since the world is very hot indeed. Not a huge amount of what’s interesting about the world made it into either of its RPGs. Meanwhile, Morrowind created an interesting world that still sticks in my mind to this day, despite the game being ugly by today’s standards without mods, and more than occasionally janky even with them. STALKER is the same, inspiring me to read Roadside Picnic (Itself a fascinating world.)

You don’t have to nail down every point. You don’t have to dot every i, cross every t. But if you have an interesting, breathing world, this will be noted.

A Consistent Lo-Fi Aesthetic Trumps A Shining Turd

Dat UI…

If you listen to some folks, 60 FPS stable is the holy grail. It doesn’t matter if it plays like shit, or wasn’t actually the intended framerate, it’s the holy grail, shut up and drink from it. We’re in the age of 4K and… Look… Fidelity only gets you so far. Stability? That’s good. You definitely want to be aiming for stability. But you can make lo-fi work for you. Let’s take a brief look at some examples, shall we?

Ah, Lemmings. Simple gameplay on paper, a bastard by design in the later stages (and some of the early ones, if we’re being honest.) When I say “Lemmings”, nearly everybody I’ve talked to who hasn’t said “What?” will generally say nice things about Lemmings 1 and 2. Lemmings 3D, on the other hand, I don’t hear so many nice things about. Partly because it was largely forgotten, partly because, like a few later Lemmings titles, it tried to go back to simpler times (and that didn’t go down terribly well), but partly because… Well, a messy UI, for a start. Look up some Lemmings footage, of the first two games, and note how, while individual lemmings are tiny (a challenge to animate a tiny sprite, the story goes), the UI is clear: Here’s what the thing is, here’s how many you have, here’s your In, here’s your out.. The same information is represented in 3D Lemmings above, but in a manner that, subtly, is less fun.

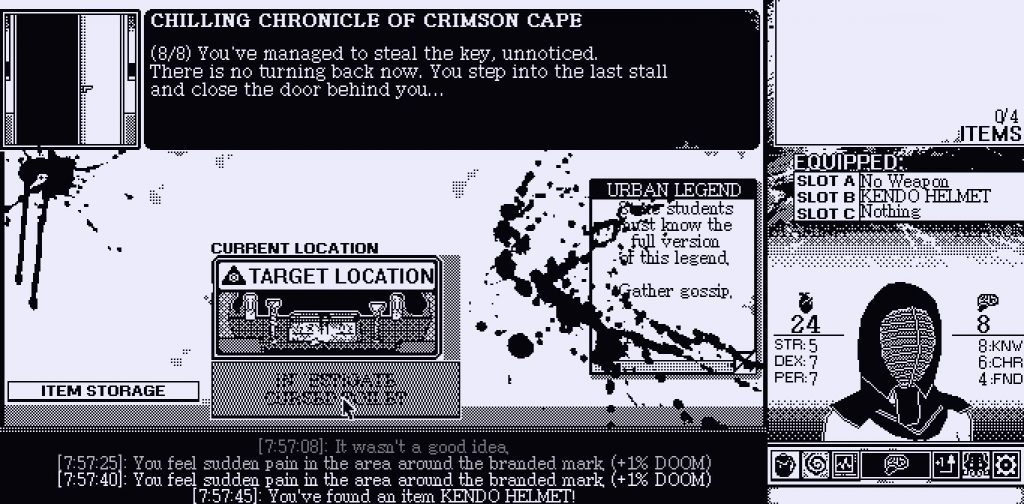

See, on the one hand, exploring school in a Kendo Helmet looks silly. On the *other* , it’s protection. More important than my fashion sense.

World of Horror, despite having 2 bits to its art, stands out to me, because it’s going for an aesthetic, and it nails it, all while remaining clear on the UI front (I know what things do.) It’s the same with Reigns (Polygons), Interstate 76 (a game I, to this day, endlessly bitch about not having a decent, faithful PC remake of, despite knowing the futility of asking this on multiple levels), and Wipeout 3 (Which doesn’t have many polygons, but uses them, and its UI, to maximum effect.) I remember Veil of Darkness more than I remember the remake of Alone in the Dark, because it not only had a relatively clear UI, it also had one that fit its atmosphere. Diaries of a Spaceport Janitor sticks in my mind because of its unique stylings, combined with an interesting world. My Lovely Daughter, Darkest Dungeon, Guild of Dungeoneering, and Deep Sky Derelicts all use hand drawings as an inspiration in one form or another, from the cel-shaded stylings of Mike Mignola, to comics of the 90s, to gothic inkwork, to the idea of drawing your own maps as a dungeon master on graph paper.

If you have an aesthetic, while being clear about your information, you’re going to be remembered more. Not just because more people are able to play your game, but because you’ll have stuck in their minds.

In Closing

Look at games of the past. You don’t have to slavishly copy them… In fact, to do so slavishly would indeed be a bad idea. But understanding what makes a game interesting, or worth examining, or even worth taking as “A lesson in what not to do” is one of many tools in the developer toolkit that is your brain, and, honestly? Exploring that is fun. Well, it is for me, anyway, otherwise I wouldn’t be doing this job.

Hopefully, I’ve instilled a little of that joy in exploring it in you, too. Enjoy the ride, you may well end up better off for it.