I always feel nervous talking about game design, because, even as a critic who has examined, not just consumed, a lot of games, there’s always this voice saying “Nah, mate, you know noooothing.”

But y’know what? Fuck that voice, it’s time to talk horror. Specifically, how horror games are hard to do well, and some of the most common pitfalls.

No Individual Element Will Make A Game Horror

This is one of the most common ones, and, honestly, a flaw which many game designers can fall into even at the best of times… Your ingredients won’t work well if they don’t mix well. In fact, when adding a tool into the toybox, it can be very important to consider what it does. Let’s take, for example, the staple of many first person horror games: The Shit Light. The Shit Light (be it matches, oddly ineffective flashlights, or the phone-as-flashlight), just by the virtue of its addition, constrains you. And it constrains you, in many cases, more often than it frees you. You do, in fact, still have to pay attention to not just being empty rooms, or rooms that make no sense, or rooms that are fucking hard to navigate even without this inconvenience. You do, in fact, have to still pay attention to your gribbley, beastie, ghost or ghoulie, because they’re going to be lit up at some point. But now, everything you want the player to look at has to be easily covered by… Your shit light.

Conarium has, to be sure, its creepy moments. Unfortunately, only one of them really *relies* on your flashlight dying as an effect.

Now, here’s a question: Do you, in fact, need that shit light? Why is it there? I ask, because, funnily enough, this shit light ends up conflicting with another facet that often goes together with Shit Lights… The Highly Scripted Scare. A scare is, sadly, no good if you can’t experience it. Oh no, the… Er… What was that again? I couldn’t really tell, my light was too shit, and so it wasn’t scary. Was it sudden? Was it a jumpscare? Oh, er… Couldn’t really tell you.

Am I saying the Shit Light has no place anywhere? Well… No. In some games, it serves as a risk reward mechanic (The monsters can see you more easily, but you can interact with things.) In others, it’s a warning sign (The monster makes the light not work right.) In others still, it’s a light, but it’s not shit.

Sadly, just as there are ways to make a Shit Light useful, you equally have to take care not to turn it into arbitrary difficulty… Tattletail being a good example, as well as one that conflicts narratively. Not only is it a pretty shit light, not only does it have a nasty habit of winking off whenever Mama Tattletail is nearby… Turning it back on is noisy as hell. So, when are you most likely to recharge it? Er… When it winks out. When Mama Tattletail is going to speed her Furby ass toward you from nowhere. Because yes, occasionally it will just wink out on its own too.

Here’s the thing: It’s being wielded by a child. How many kids have you heard of who wouldn’t look for a different light, any other kind of light, that maybe doesn’t make noise which every kid knows is fucking asking for boogeyman induced death?

This, funnily enough, is a good segue into the next portion.

Because Reasons Doesn’t Cut It

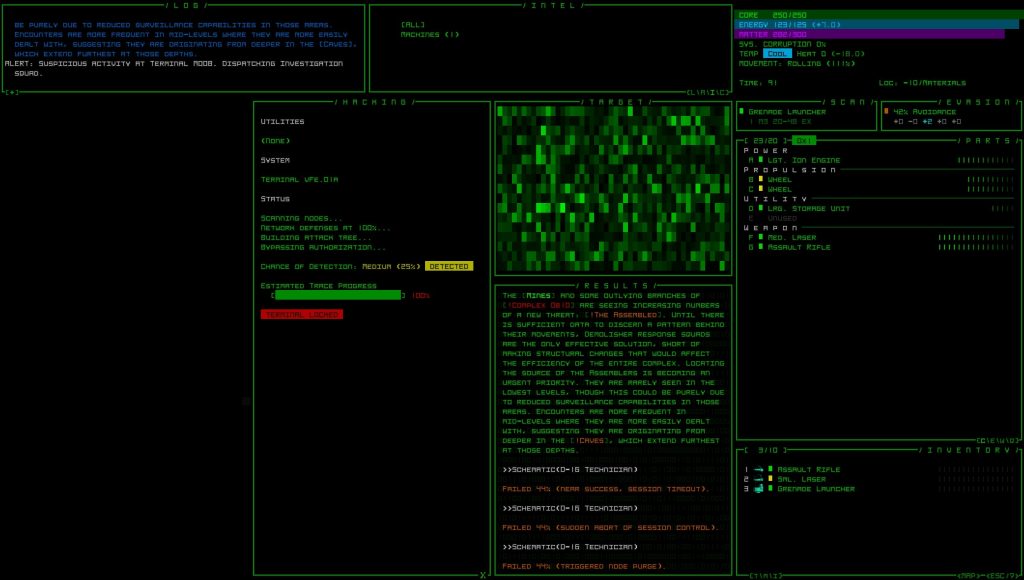

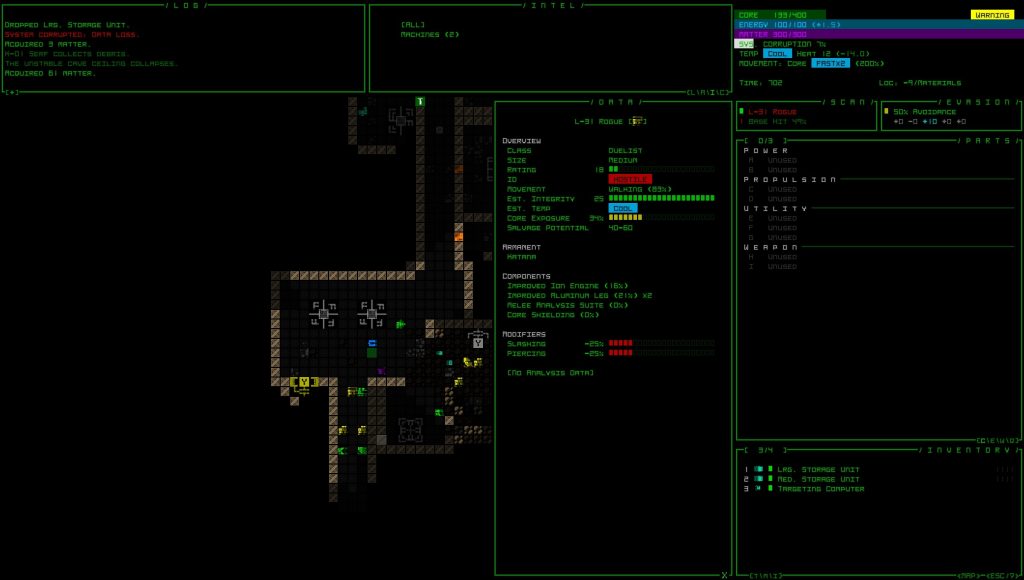

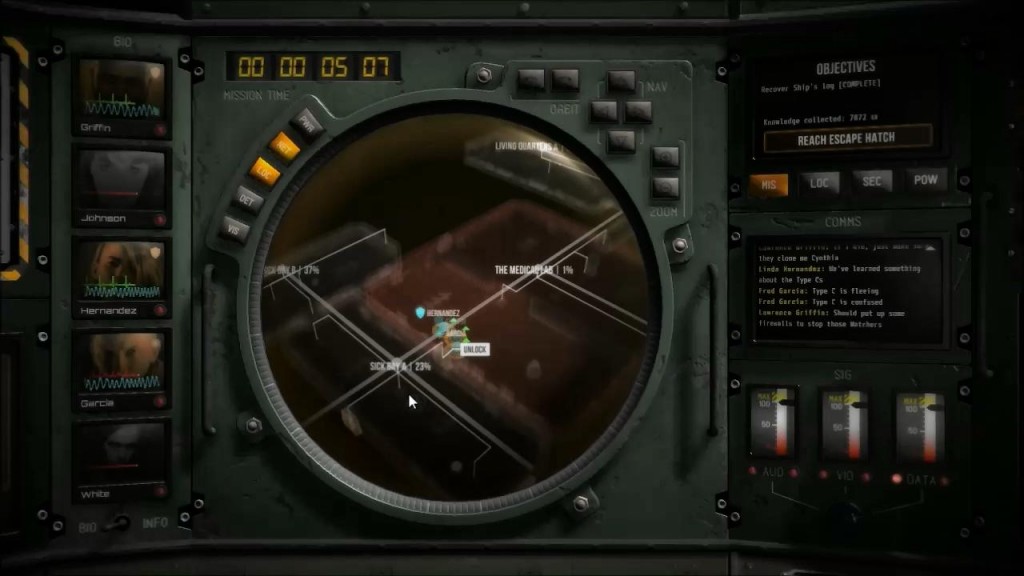

A lot of both STASIS and its sequel CAYNE have major story elements that, sadly, fit very much under this category. This, for example, happened because a serial killer was knowingly employed by the captain of the ship, and his mulching the corpses somehow led to a sentient fungus that taints everything it touches. Because reasons.

One thing I see a lot of is a terminal lack of critical thinking on the part of the protagonist (Both by the writer/designer, and, as a consequence, the protagonist.) Tattletail is, as we’ve noted, an example, but it’s not the only one by a long shot. Part of this is, again, the use of an element of games design without thinking about the consequence (No, I do not, in fact, have to give a flying fuck about your amnesiac blank slate. Especially if they talk, cementing that they are not me.) But, unfortunately, horror is less horrific when you either don’t care about the protagonist, or think they’re… Well, candidates for a Darwin Award. Oh, hey, I’m in this haunted mansion… Why am I in this haunted mansion?

No, really… Why? This isn’t a question you can answer with “Just Because.” You don’t even have to work terribly hard at it. Let’s take SIREN, for the PS2, as an example of this. A lot of the characters are there because… Well, they live there, and shit’s gone to hell. They’re one of the “lucky” few, so the game quickly defines them, moves on. They’re defined by survival and escape. Kyoya Suda, one of the main characters, is a teenage mystery buff who decided to check out Hanuda because of the urban legends. He can’t leave, because he is, technically, dead. Tamon Takeuchi, similarly, is motivated by the legendry, but what keeps him in Hanuda is a combination of arrogance and professionalism. He will discover what happened!

Not all of them get equal screentime, not all of them survive. But all of them can have their goals, and even reasons why they can’t leave, established in a single sentence each.

The Shrouded Isle works as a horror styled game because there’s *reasoning* behind the evil. And, of course, it’s not *considered* evil by the protagonist. After all, few good villains *consider* themselves wrong.

Similarly, “Because” doesn’t cut it for any element. Why is this house haunted again? Hadn’t they lived there for years with no trouble? Oh, they had? Huh. Why the doll-head jumpscare? Oh, there’s no real connection there? Ummm… Okay, beyond the momentary shock, that’s just confusing me. It’s not contributing to the mood. Now, not every question has to be answered. But at the very least, you want to ensure there is reasoning behind even your gribbley(s). Wobblyhead McSmudgyShadow does not, funnily enough, scare me, because firstly, I know nothing about him, and secondly, he looks silly. Also, why is he walking when he’s made of smokey shit? Why, when he has clearly demonstrated he can run fast enough to get into my face, then down the corridor before I can blink, is he slowly stalking me?

Oh, you didn’t think about that? No. No you didn’t. Consider this, though… The Necromorphs would just be ordinary monsters, if it weren’t for the thought put into their lifecycle. Consider: Not only are they twisted versions of us that are functionally immortal… Not only are they highly infectious and it isn’t obvious at first when someone is infected… You quickly realise that the only major reason limb trauma works so much better than just pumping them full of hot plasma death is because the thing, the thing controlling them as one, decides they’re no longer useful for their purpose… Namely, turning you into them. Conversely, part of the reason The Thing: The Videogame didn’t work is because the idea behind detecting Thingism (An established, pre-thought idea) was ruined, unfortunately without thinking too heavily about the consequences, by Thingism being a plot trigger, making your blood test items completely worthless.

See how these factors are starting to tie together. Oh… BOO!

Segue.

Sound And Fury, Signifying… Nothing.

I’ve already mentioned how jumpscares, like any other element, can feel completely without context, without reason. What I haven’t mentioned is the noise element. Christ, these things are loud. And while there is a reason for this, it’s a pretty crap one: For shock value.

AND SUDDENLY DEATH AND BLOOD

Shock, funnily enough, is not fear. It’s not unsettling. It’s not disturbing. It’s just “Thatwasloud oh, it’s gone, I can carry on now.”

Like the monsters, like the character, like the setting, like… Well, everything, context is important. I hear a baby giggling in a house, I am, funnily enough, not going to say “Wow, that’s creepy.” I’m going to say “Ah, yes, the giggling baby cry, stock in trade of someone who wants to put me off balance and hasn’t set this up in any way, shape or form.”

Well, no. What I’m actually going to say is “…Huh. [Moves on without further comment]”

However, if I am aware that there was indeed a dead child… Say… A particularly sadistic dead child, who is now a particularly sadistic ghost, then every time I hear them giggle, even if nothing happens, I am instantly in “Primed for bad shit” mode. A jumpscare, or even a cat-scare (so named because very often, a fake scare involved a startled cat in horror movies) works best when you’re already prepped for it by the atmosphere.

Inmates, a recent game I reviewed, decided that it was a good idea to do several things at once. None of them are awful on their own, but together, they added up to unpleasantness enough that I just got annoyed. Firstly, control was taken away so a monster could get me. Okay, this isn’t always a bad thing. Many’s the time a game has ambushed me in an end-of-level segment or cutscene, and mostly, I’m alright with this. It also decided to give the monster in question the most minimal prep-time (a droning infodump from a few minutes ago), so, when the protagonist yelled “OH NO, IT’S ROY”, my eyebrow raise knocked some plaster from the ceiling. The monster in question did that “I suddenly run really fast” thing, screamed in my face, and then… Almost a minute of a high pitched, tinnitus like sound. Also a slow cutscene of being dragged.

On their own, pretty much everything except the high pitched noise (Which just annoys and hurts the ears, rather than signalling a return to consciousness/dizziness) could have worked. If Roy had been prepped better, if I’d had a reason to care about Roy (Sir No Longer Appearing In This Production), if, for example, he was round the corner rather than doing the lightspeed jog the moment the door opened, then it probably would have worked better. As it is… Well, that was it for me, and not because it was too spooky. Mainly because I was just annoyed at how arbitrary it was.

An example of good sound usage comes from Zero Escape: Zero Time Dilemma, where being showered in acid is left to the imagination… And some particularly gruesome soundwork.

Done well, sound is your best friend. The character’s footsteps echoing in a haunted castle, for example, really drive home how alone you are. But they, like everything else, require context, even if that context isn’t yet known to the player. Why is that wall… Scratching? Why do I hear… Whispering in this library? Like… Not even normal whispering… Bass whispering. Wait, is that gribbley saying things a human would have been saying in their position? Is it… Was it human?!?

Oh nooooooooooo!

A Curated Experience

When you get right down to it, horror seems to work best when it’s a linear, curated experience. In an open world, you have to work so much harder, so much tighter, to keep scaring people. Look at a lot of zombie games like Dead Island or the like. Most of the time, apart from maaaaybe their introductions, the zombies aren’t scary. They’re obstacles.

Pictured: An entire block, in the first of its three flavours, in which you will hunt for the thing you actually need to see.

And yeah, despite what marketing may have you believe, there’s room for linear, curated experiences. They’re fine. Heck, some of the best fun I’ve had in recent years haven’t been sandboxes, or open world RPG extravaganzas. But trying to have your cake and eat it is probably going to cause pain. For example, Joana’s World, another horror game I reviewed, had an entire block of houses and a park. Wiiiith the small problem that the game’s events only involved two of those houses. It also wouldn’t allow you to do things until the plot mandated you do them, such as not being able to pick up your front door keys or flashlight until… Well, you needed them, even knowing that you needed them beforehand. The first because who doesn’t pick up their front door keys before they prepare to go out (unless they’ve forgotten), and secondly because this is a first person horror game, and it is a flashlight.

Equally, though, we tie back to Because Reasons, with the note that when you block something off, there has to be a reasonable, in context explanation for it. My personal favourite for slightly nonsensical obstacles is one that you see time and time and time again… The hospital bed/curtain. Sometimes they’re in piles (You Are Empty, some Silent Hill games), and this is pretty reasonable. But more often, they’re just… There. You can’t climb them, even though they’re short. You can’t move them, even though they’re wheeled.

“But Jamie, not everything can be moved in a videogame, or chaos will ensue! Rains of frogs, cats and dogs living together!” True. But if you’re reduced to “A hospital bed” rather than… I don’t know, a barricade, a big hole in the floor, barbed wire (don’t laugh, I’m sure you could find a context for that!) … Something that isn’t easily moved, but makes sense for what’s going on or where you are, then you’re mostly going to have to rely on that other aspect of subtle game design… Making the bit blocked off with a single trolley and a hospital curtain less interesting.

Remember, you can just block players off from somewhere. It’s fine. Really it is.

Some Final Caveats

Example of happily being proven wrong: If you’d told me, pre Screwfly, that this would get my nerves racing, I would have laughed and laughed.

Okay, so I’m picturing some folks getting a little purple in the face while reading this, and others may well have peaced out already, so let’s finish this up with some simple, final points. First up, if you actively enjoy any of the games I’ve mentioned as having unfun elements for me, good for you, keep on doing that! I’m a reviewer, not the fun police.

Secondly, everything I’ve described here are guidelines, not rules. You see a way you think you can make a relatively open game genuinely creepy, cool, work at that, lemme know how it goes. These are, however, guidelines based on both common sense, study, and experience. But, again, I am not the fun police, you want to make a game with a contextless spoop, walking very slowly around an entire block of flats, while hunting for the Eight Random Items We’re Not Telling You About Beyond “Find Eight Thingumajigs” and babies are giggling in a creepy fashion almost constantly, then cool. Just don’t expect me to touch the damn thing.

I hope these have helped. I hope these have illuminated, and I’ll leave you with one final piece of advice: Play horror games. Even some of the ones lambasted. Examine how they make you feel, ask why they make you feel that way, and how they’ve made you feel that way. And if you decide to make a horror game, ask whether or not you can apply something as is (You don’t, for example, need your game to be in a dark place), and see what your players feel.

Happy Halloween!

Filed under: Game Design by admin

Become a Patron!